MAOA–Environment Interactions: Results May Vary

David Goldman and Alexandra A. Rosser

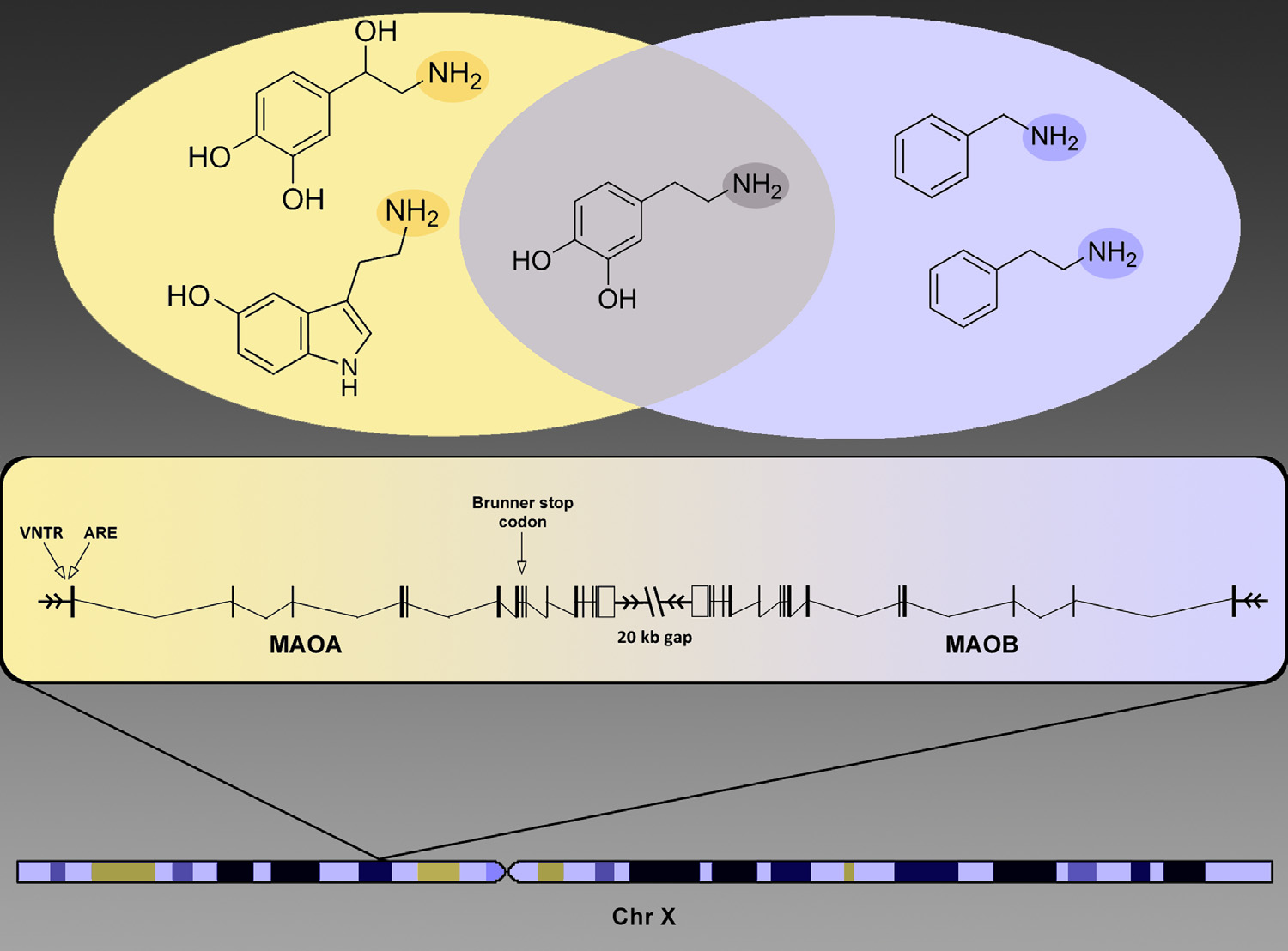

In a seminal article, Brunner and colleagues (1) discovered a stop codon unique to one Dutch family leading to altered metabolism of monoamine neurotransmitters and antisocial behavior in hemizygous males (Figure 1). Discovery of this rare functional variant was followed by the detection of a common functional variable number of tandem repeat locus that was associated to behavioral dyscontrol, especially in the context of stress exposure (Figure 1). In 2002, Caspi et al. (2) reported the first powerful demonstration of gene–environment interaction in behavior by showing that childhood maltreatment predicted antisocial behavior in men as a function of monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) genotype. This finding has proven to be a veritable cornucopia or prototype, spawning myriad studies that have sought to address the issue of whether the combined effects of low expression MAOA genotypes and stress are additive or interactive along with studies of the environment’s interaction with many other genes. Under the additive model, 2 � 2 ¼ 4, but as is well understood, interactions can be subadditive (e.g., 2 � 2 ¼ 3) or superadditive (e.g., 2 � 2 ¼ 10).

In this issue of Biological Psychiatry a positive MAOA-maltreatment meta-analysis is juxtaposed with a negative MAOA-maltreatment study conducted in a single, large, well-characterized sample. In their meta-analysis, Byrd and Manuck (3) evaluated 27 peer-reviewed studies on MAOA-maltreatment interaction published between 2002 and 2012. Overall, these studies supported the original MAOA–maltreatment interaction in males and showed a similar, although less robust trend in females. A minority of studies reviewed by Byrd and Manuck reported null or opposite results, highlighting several important functions of meta-analysis. A more panoramic view can point to overall consistency, even on a lowest common denominator (meaning crude) dependent variable such as antisocial behavior. Moreover, meta-analysis can reveal false positives or false negatives, time trends, and publication bias. Meta-analysis also enables more accurate estimation of effect size; this is particularly important for the estimation of interaction effects, which requires large samples. Also in this issue of Biological Psychiatry, Haberstick et al. (4) report lack of interaction between MAOA and childhood maltreatment drawing from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health is a large (n ¼ �26,000), nationally and epidemiologically representative sample tracking adolescents through adulthood—a goldmine for understanding the effects of predictors and their interactions on common behaviors. Studying 3,356 white and 960 black subjects from within Add Health, Haberstick et al. justifiably argue that some replications based on smaller samples could be false positives, although one previous positive study, the Avon Longitudinal Study on Parents and Children, involved a larger number of subjects (3). One problem that meta-analysis can partially address is that publication bias may be afoot in situations where replications are concentrated among smaller studies and earlier studies, problems addressed by Byrd and Manuck, who found that the MAOA–maltreatment interaction finding remains robust to the addition of many (�93!) studies of null effect and equivalent sample size and that no effect of time of publication was evident.

The qualitative and imperfect nature of behavioral measures and exposures degrades our ability to detect the interaction of a gene. Haberstick et al. constructed a composite antisocial index based on extensive information both retrospectively and longitudinally in childhood and young adulthood (4). Nevertheless, the data on which the index is constructed include convictions for violent offenses, conduct problems, and adult antisocial behaviors —items that are influenced by different sources of “noise.” For example, respondent bias and sociocultural factors influence the expression of antisocial behavior and the consequences. Several positive MAOA–maltreatment studies, including the original study by Caspi et al. (Dunedin Longitudinal Cohort) and Enoch et al. (Avon Longitudinal Study on Parents and Children) were conducted on more homogeneous samples (2,5). The one near constant in all interaction studies has been MAOA genotype; however, we cannot expect the maltreatment predictor variables and behavioral outcomes in the various studies to equate, and there may be modifying variables of unknown effect. Failure to replicate a genetic association does not prove complexity of causation. However, one must consider the possibility that the gene’s effect on complex behavior is small and at the mercy of unmeasured influences. How to proceed: isolate the effects of genes and environment on brain function and behavior by better stratifying for factors of strong effect (for example, severe maltreatment) and by identifying phenotypes closer to the level of the gene but relevant to the gene–environment interaction and by the use of model organisms in which genotype, including genetic background and exposures, can be controlled. Fortunately, this is exactly the turn that MAOA research has taken. Although some continue to define the broad effects of MAOA on behavior in population samples, others are identifying neurogenetic mechanisms. Neuroimaging studies have yet to demonstrate MAOA– maltreatment interaction, but they have confirmed that MAOA alters function of brain regions involved in emotion and provided a genetic clue as to why some brains respond more strongly to maltreatment than others. Several years ago, Buckholtz et al. (6) reported that males carrying low-activity MAOA genotypes had dysregulated amygdala activation and enhanced functional coupling with ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Their functional coupling predicted increased harm avoidance and decreased reward dependence. MAOA–maltreatment interaction studies have not always accounted for the multifaceted relationship between gender and MAOA. At the level of brain function, Buckholtz et al. found that MAOA low activity genotypes more strongly alter the brain activation of male subjects (6). Haberstick et al. studied only male subjects, and most studies meta-analyzed by Byrd and Manuck focused on males or both sexes (3,4). However, 7 of the 27 studies were exclusively female (3). At the level of the gene, males and females differ in copy number, one of the two copies in females being randomly inactivated in different cells. As shown in Figure 1, MAOA and MAOB are oriented in tail to tail (3′ gene end to 3′ gene end) on the X chromosome (7). This gene configuration has been phylogenetically conserved in mammals, with the two enzymes metabolizing a partially overlapping series of monoamine neurotransmitter substrates. Thus, males are hemizygous for either a low or high activity MAOA allele, whereas many females are heterozygous and thus have intermediate enzyme activity. Some investigators arbitrarily lump heterozygotes with one of the homozygotes, others treat the three genotypes as distinct predictors, and others, as is probably most biologically accurate, regress behavioral outcome against the number of copies of the low activity allele. At the level of social context and exposures, males and females differ; females are more likely to experience sexual trauma, whereas males are more likely, because of sociocultural factors, to exhibit aggression.

Finally, MAOA activity appears to be modulated by testosterone. An androgen responsive element is found in the MAOA promoter. The ability of the low-activity MAOA to increase aggressive behavior is strongly influenced by interaction with high testosterone levels found in some males but seldom found in females (8).

The effect of MAOA on antisocial behavior might therefore be obscured in studies that included prepubertal males (5). The benefits of understanding the nuances of the effects of MAOA are likely great. Low-activity alleles are common in all populations surveyed thus far. Selective MAOB inhibitors are used for Parkinson’s disease, whereas selective MAOA inhibitors are used to treat depression and anxiety (9). Dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters metabolized by MAO enzymes have protean effects on behavior. The functional MAOA variable number tandem repeats and rare MAOA stop codon are part of the stuff of the many heritable behaviors influenced by these monoamine transmitters. Deciphering the genetic code of behavior requires the identification of functional loci at many other genes, and probably at thousands of genes. It will also require the broad-scale gene–environment and finer scale neuroscience studies that have taken us to a partial understanding of the role of MAOA in behavior.

Figure 1. The monoamine oxidase (MAOA and MAOB) genes are located 20 kb from each other on the p arm of the X chromosome in tail-to-tail orientation. The variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) and androgen responsive elements (AREs), responsible for differential behavior of MAOA, are located within the gene’s promoter region. The Brunner stop codon, which resides in the MAOA gene’s eighth exon, results in complete dysfunction of the gene. In the Venn diagram: amine groups (NH2) of molecular substrates are highlighted. MAOA preferentially degrades norepinephrine (top left) and serotonin (bottom left), whereas MAOB preferentially degrades benzylamine (top right) and phenylethylamine (bottom right). Both enzymes degrade dopamine (middle).

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential

conflicts of interest.

1. Brunner HG, Nelen M, Breakefield XO, Ropers HH, van Oost BA (1993): Abnormal behavior associated with a point mutation in the structural gene for monoamine oxidase A. Science 262:578–580.

2. Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R (2002): Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science 297:851–854.

3. Byrd AL, Manuck SB (2014): MAOA, childhood maltreatment, and antisocial behavior: Meta-analysis of a gene–environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry 75:9–17.

4. Haberstick BC, Lessem JM, Hewitt JK, Smolen A, Hopfer CJ, Halpern CT, et al. (2014): MAOA genotype, childhood maltreatment, and their interaction in the etiology of adult antisocial behaviors. Biol Psychiatry 75:25–30.

5. Enoch MA, Steer CD, Newman TK, Gibson N, Goldman D (2010): Early life stress, MAOA, and gene–environment interactions predict behavioral disinhibition in children. Genes Brain Behav 9:65–74.

6. Buckholtz JW, Callicott JH, Kolachana B, Hariri AR, Goldberg TE, Genderson M, et al. (2008): Genetic variation in MAOA modulates ventromedial prefrontal circuitry mediating individual differences in human personality. Mol Psychiatry 13:313–324.

7. Grimsby J, Chen K, Wang LJ, Lan NC, Shih JC (1991): Human monoamine oxidase A and B genes exhibit identical exon-intron organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:3637–3641.

8. Sjöberg RL, Ducci F, Barr CS, Newman TK, Dell’osso L, Virkkunen M, Goldman D (2008): A non-additive interaction of a functional MAO-A VNTR and testosterone predicts antisocial behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:425–430.

9. Nowakowska E, Chodera A (1997): Inhibitory monoamine oxidases of the new generation. Pol Merkur Lekarski 3:1–4.

www.sobp.org/journal

برای دریافت خلاصه مقاله به صورت PDF کلیک کنید.